Festive Lights: Was Christmas cancelled?

Christmas awakens the strongest and most heartfelt associations. The services of the Church about this season are extremely tender and inspiring. I do not know a grander effect of music on the moral feelings than to hear the full choir and the pealing organ performing a Christmas anthem in a cathedral, and filling every part of the vast pile with triumphant harmony.

Christmas awakens the strongest and most heartfelt associations. There is a tone of solemn and sacred feeling that blends with our conviviality and lifts the spirit to a state of hallowed and elevated enjoyment. -Washington Irving

The thought of re-sizing this winter festive celebrations is shaping in everybody’s mind. Could you be persuaded to leave the Festive Lights’ switched off this Christmas? As we are reaching the end of this strange year, we have to admit that 2020 is ranking really low on festive celebrations. Visiting loved ones or meeting friends and peers at Christmas seems a luxury as we constantly learn that celebrations and hugs are best held on Zoom.

Was Christmas ever cancelled?

For two millennia, Christmas has been celebrated on December 25 and in 2020 is a tradition for a sacred religious holiday for some but a worldwide cultural and commercial phenomenon embraced by all.

Decorating your Christmas tree, switching the lights on, going to church, sharing good wishes, and cooking meals with family and friends while waiting for Santa Claus to come down on the chimney, are all part of the Christmas tradition.

A quick look into the English and American national archives, shows us times in history when Christmas was cancelled and how it changed the course of history.

When Christmas was cancelled, parties turned into riots, which led to rebellions in 1647 and 1648, parties led to riots, and caused the Second Civil War. King Charles lost the war, put on trial and was executed. The revolution in Britain and birth of the republic of Ireland are all historic facts because the Christmas was cancelled.

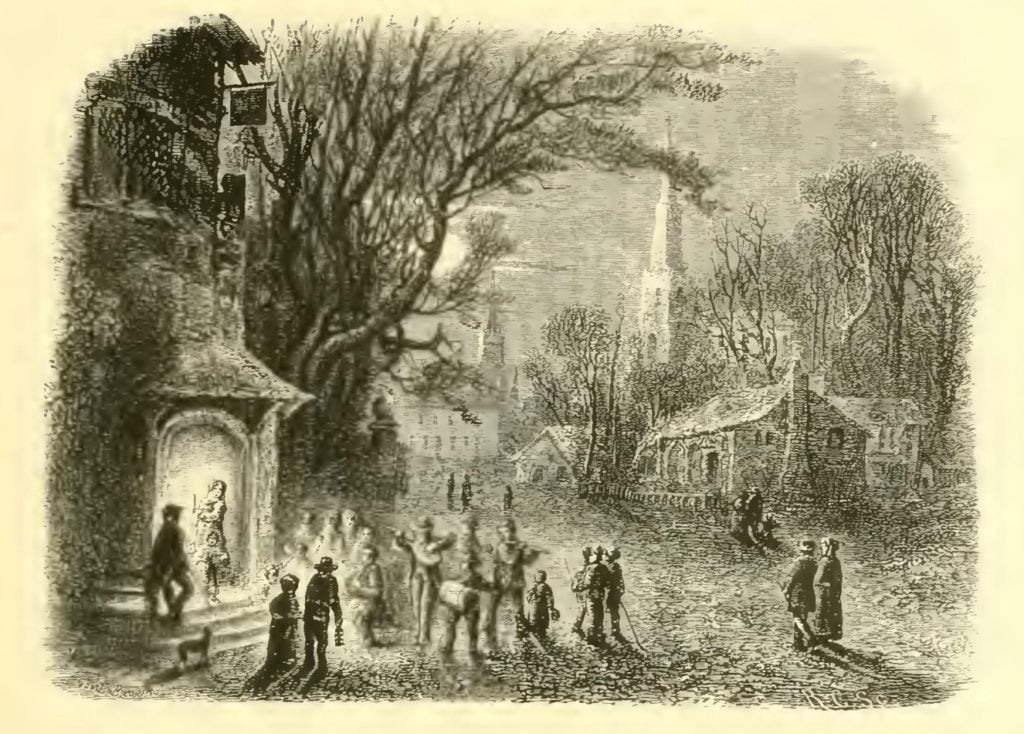

One of the most anticipated days of the year, December 25, Christmas Day, has been a federal holiday in the United States since 1870. Christmas was not a holiday in early America, as the English separatists that arrived in America in 1620 brought along their Puritan beliefs. Boston, a stop on a major trade route with the West Indies during colonial times, outlawed Christmas celebrations for 22 years. Anyone sharing the Christmas spirit was fined 5 shillings. There were no Christmas trees in any household between 1659 and 1681. Imagine Boston with no Christmas Lights!

To celebrate Christmas, you had to travel down on the East Coast, to the first settlement in the Americas, the Jamestown settlement, in the Colony of Virginia, where Christmas celebrations were in full swing.

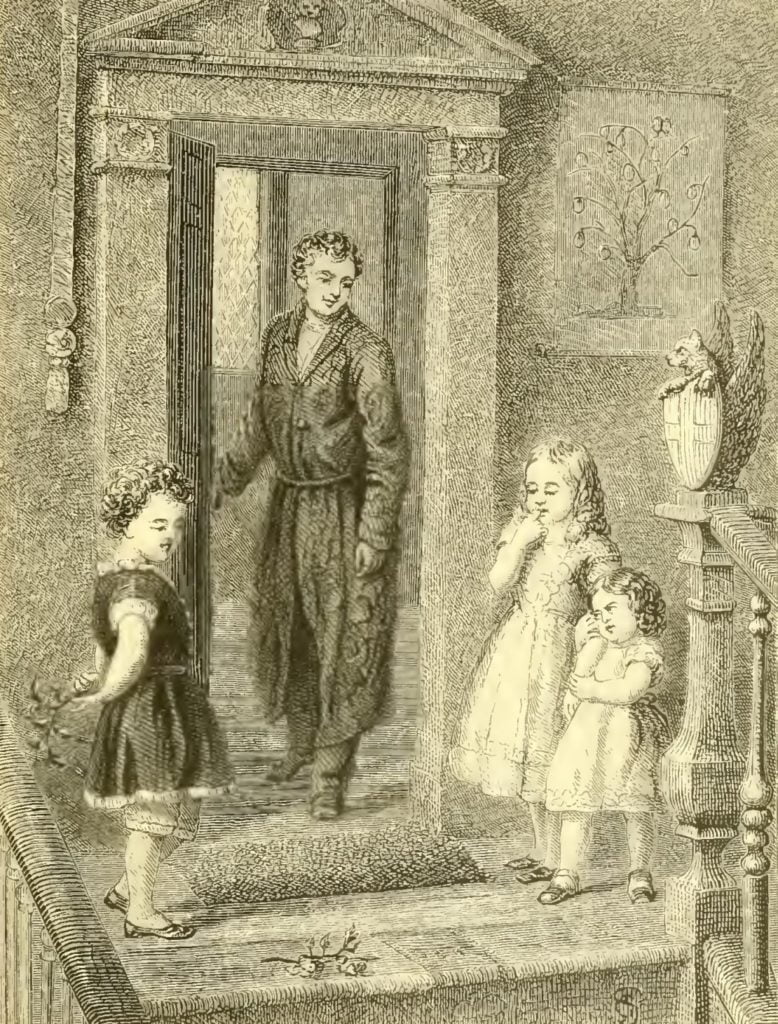

Washington Irving Re-Imagined Christmas

With high unemployment, the early 19th century was filled with economic uncertainty, gang rioting and class conflict. The city’s first police force in response to a Christmas riot was established in 1828, by the New York city council. This is when upper classes changed the way Christmas was celebrated in America. But in 1819, best-selling author Washington Irving wrote about the celebration of Christmas in an English manor house. The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon, gent., featured a squire who invited the peasants into his home for the holiday, a metaphorical contrast to the reality of the American society. This imaginary chronicle of an English Manor House was reflecting Irving’s mind, and his solution to resolve the conflict between different social status, by celebrating a peaceful Christmas regardless of wealth or social status.

It is fair to say that Americans re-invented Christmas, and took it from its initial “carnival holiday” form into a peaceful family day celebrations, filled with love, fine cuisine. Every year since, Americans dwell into the magic of Christmas and switch the festive lights on without fail.

But is old, old, good old Christmas gone?

NOTHING in England exercises a more delightful spell over my imagination than the lingerings of the holiday customs and rural games of former times.

Of all the old festivals, however, that of Christmas awakens the strongest and most heartfelt associations. There is a tone of solemn and sacred feeling that blends with our conviviality and lifts the spirit to a state of hallowed and elevated enjoyment. The services of the Church about this season are extremely tender and inspiring. They dwell on the beautiful story of the origin of our faith and the pastoral scenes that accompanied its announcement. They gradually increase in fervor and pathos during the season of Advent, until they break forth in full jubilee on the morning that brought peace and good-will to men. I do not know a grander effect of music on the moral feelings than to hear the full choir and the pealing organ performing a Christmas anthem in a cathedral, and filling every part of the vast pile with triumphant harmony.

There is something in the very season of the year that gives a charm to the festivity of Christmas. At other times we derive a great portion of our pleasures from the mere beauties of Nature. Our feelings sally forth and dissipate themselves over the sunny landscape, and we “live abroad and everywhere.” The song of the bird, the murmur of the stream, the breathing fragrance of spring, the soft voluptuousness of summer, the golden pomp of autumn, earth with its mantle of refreshing green, and heaven with it deep delicious blue and its cloudy magnificence,—all fill us with mute but exquisite delight, and we revel in the luxury of mere sensation. But in the depth of winter, when Nature lies despoiled of every charm and wrapped in her shroud of sheeted snow, we turn for our gratifications to moral sources. The dreariness and desolation of the landscape, the short gloomy days and darksome nights, while they circumscribe our wanderings, shut in our feelings also from rambling abroad, and make us more keenly disposed for the pleasure of the social circle. Our thoughts are more concentrated; our friendly sympathies more aroused. We feel more sensibly the charm of each other’s society, and are brought more closely together by dependence on each other for enjoyment. Heart calleth unto heart, and we draw our pleasures from the deep wells of loving-kindness which lie in the quiet recesses of our bosoms, and which, when resorted to, furnish forth the pure element of domestic felicity.

The pitchy gloom without makes the heart dilate on entering the room filled with the glow and warmth of the evening fire. The ruddy blaze diffuses an artificial summer and sunshine through the room, and lights up each countenance in a kindlier welcome. Where does the honest face of hospitality expand into a broader and more cordial smile, where is the shy glance of love more sweetly eloquent, than by the winter fireside? and as the hollow blast of wintry wind rushes through the hall, claps the distant door, whistles about the casement, and rumbles down the chimney, what can be more grateful than that feeling of sober and sheltered security with which we look round upon the comfortable chamber and the scene of domestic hilarity?

The English, from the great prevalence of rural habit throughout every class of society, have always been found of those festivals and holidays, which agreeably interrupt the stillness of country life, and they were, in former days, particularly observant of the religious and social rites of Christmas. It is inspiring to read even the dry details which some antiquaries have given of the quaint humors, the burlesque pageants, the complete abandonment to mirth and good-fellowship with which this festival was celebrated. It seemed to throw open every door and unlock every heart. It brought the peasant and the peer together, and blended all ranks in one warm, generous flow of joy and kindness. The old halls of castles and manor-houses resounded with the harp and the Christmas carol, and their ample boards groaned under the weight of hospitality. Even the poorest cottage welcomed the festive season with green decorations of bay and holly—the cheerful fire glanced its rays through the lattice, inviting the passengers to raise the latch and join the gossip knot huddled round the hearth beguiling the long evening with legendary jokes and oft-told Christmas tales.

How was the Christmas Dinner served?

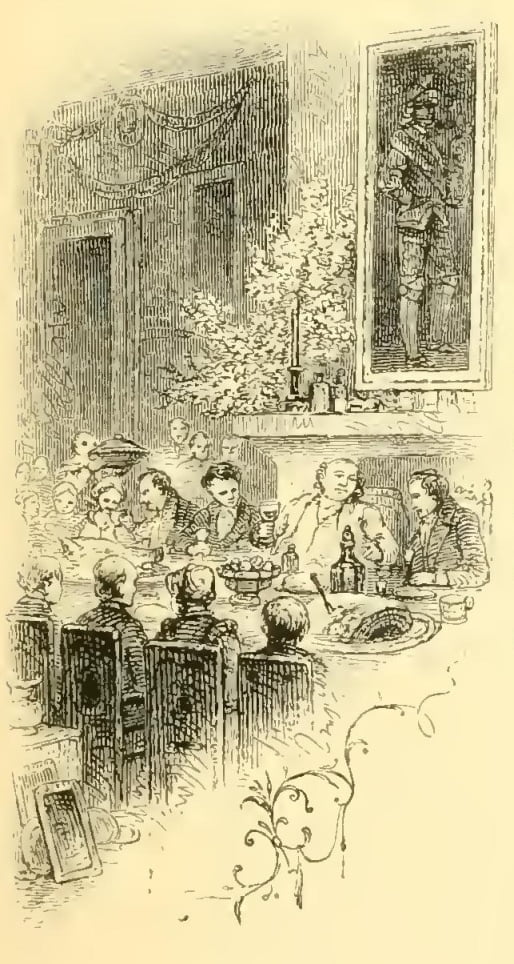

The dinner was served up in the great hall, where the squire always held his Christmas banquet. A blazing crackling fire of logs had been heaped on to warm the spacious apartment, and the flame went sparkling and wreathing up the wide-mouthed chimney. The great picture of the crusader and his white horse had been profusely decorated with greens for the occasion, and holly and ivy had like-wise been wreathed round the helmet and weapons on the opposite wall, which I understood were the arms of the same warrior. I must own, by the by, I had strong doubts about the authenticity of the painting and armor as having belonged to the crusader, they certainly having the stamp of more recent days; but I was told that the painting had been so considered time out of mind; and that as to the armor, it had been found in a lumber-room and elevated to its present situation by the squire, who at once determined it to be the armor of the family hero; and as he was absolute authority on all such subjects in his own household, the matter had passed into current acceptation. A sideboard was set out just under this chivalric trophy, on which was a display of plate that might have vied (at least in variety) with Belshazzar’s parade of the vessels of the temple: “flagons, cans, cups, beakers, goblets, basins, and ewers,” the gorgeous utensils of good companionship that had gradually accumulated through many generations of jovial housekeepers. Before these stood the two Yule candles, beaming like two stars of the first magnitude; other lights were distributed in branches, and the whole array glittered like a firmament of silver.

We were ushered into this banqueting scene with the sound of minstrelsy, the old harper being seated on a stool beside the fireplace and twanging, his instrument with a vast deal more power than melody. Never did Christmas board display a more goodly and gracious assemblage of countenances; those who were not handsome were at least happy, and happiness is a rare improver of your hard-favored visage.

The table was literally loaded with good cheer, and presented an epitome of country abundance in this season of overflowing larders. A distinguished post was allotted to “ancient sirloin,” as mine host termed it, being, as he added, “the standard of old English hospitality, and a joint of goodly presence, and full of expectation.” There were several dishes quaintly decorated, and which had evidently something traditional in their embellishments, but about which, as I did not like to appear overcurious, I asked no questions.

I could not, however, but notice a pie magnificently decorated with peacock’s feathers, in imitation of the tail of that bird, which overshadowed a considerable tract of the table. This, the squire confessed with some little hesitation, was a pheasant pie, though a peacock pie was certainly the most authentical; but there had been such a mortality among the peacocks this season that he could not prevail upon himself to have one killed.

With thanks to The Project Gutenberg of The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. by Washington Irving, Produced by Nelson Nieves and David Widger)