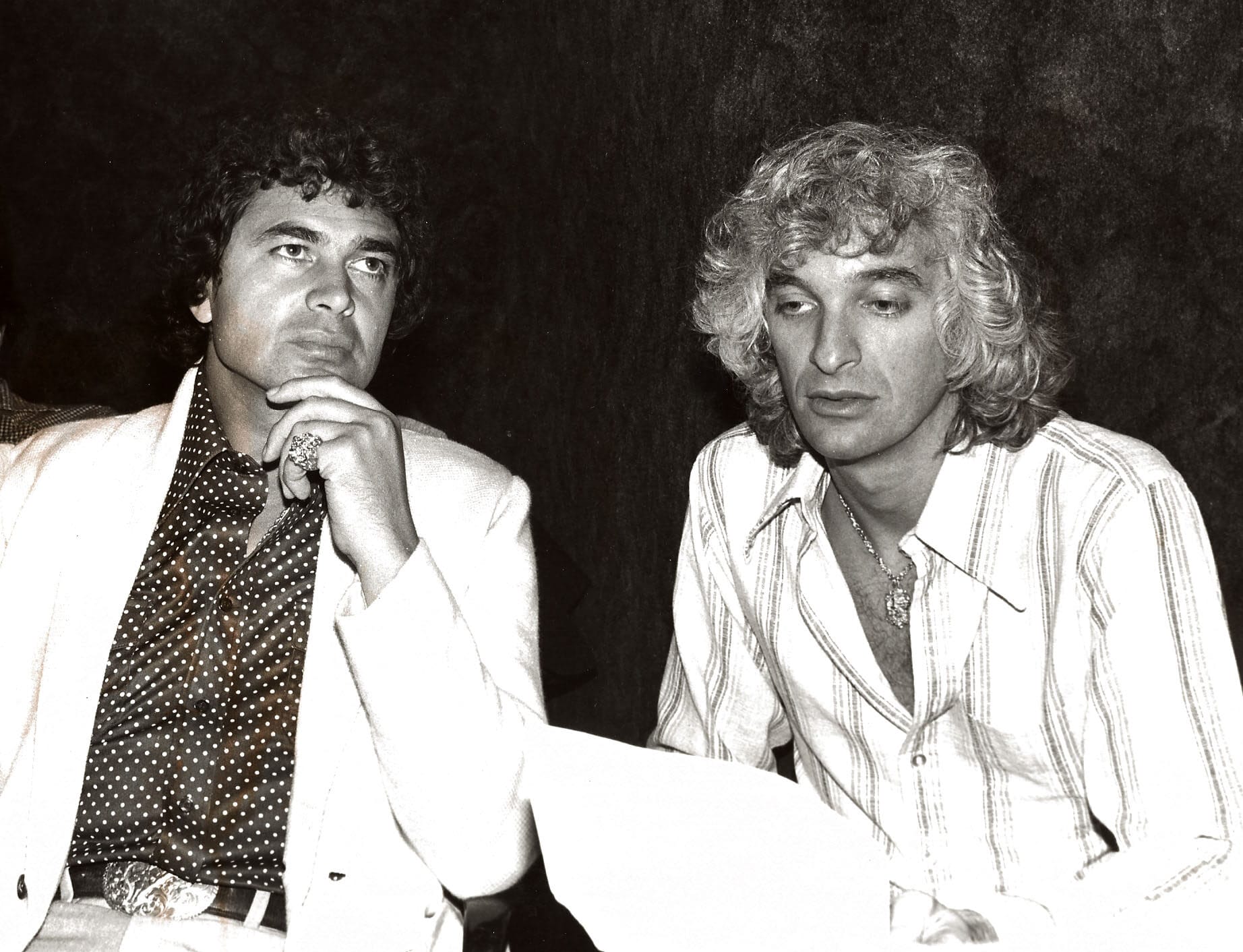

Music Producer Joel Diamond Shares His Penthouse Stories of 60 Minutes’ Don Hewitt

The creator of '60 Minutes' understood something about power that today's media executives seem to have forgotten.

The lifts at 220 Central Park South have witnessed more than their share of power conversations. But perhaps none were as quietly profound as the daily encounters between a multi-platinum record producer and the man who would prove to be one of television’s most influential figures.

For months, Joel Diamond shared these vertical journeys with a neighbour he knew simply as “Don”, a gentleman whose understated demeanor gave no hint of the media empire he’d built. Their polite exchanges were unremarkable until curiosity finally prompted the inevitable question about his companion’s work.

“I’m the creator and executive producer of 60 Minutes,” came the matter-of-fact reply that would reframe everything Diamond thought he knew about power and presence.

The Humility That Built an Empire

This moment perfectly captured Don Hewitt’s extraordinary relationship with success. Here was the architect of television’s most respected news programme, treating his revolutionary achievement as casually as one might discuss the weather. It’s a quality that feels almost revolutionary in today’s landscape of carefully curated personal brands and corporate grandstanding.

Diamond’s memories of his former neighbour offer something precious: an intimate portrait of authentic leadership in action. Whether Hewitt was enthusiastically unrolling what Diamond diplomatically describes as “rather unattractive” carpet samples across their shared lobby, or inscribing a book with characteristic self-deprecation (“Joel, if your neighbour likes your book, how bad can it be?”), his approach to influence was refreshingly human.

The penthouse Diamond has called home for two decades became something of a salon for entertainment industry luminaries, all drawn by both the spectacular Central Park views and their host’s remarkable stories from music’s golden era. Today, that same residence holds the distinction of being America’s most expensive residential sale, purchased by hedge fund billionaire Ken Griffin – a detail that speaks to the rarefied world these conversations inhabited, yet somehow never defined them.

Diamond himself embodies this intersection of success and substance. From his early days as what he calls “a stuttering high school nerd in Passaic,” selling life insurance by day whilst performing at weddings by night, to negotiating David Geffen’s first million-dollar deal and producing 47 gold and platinum albums, his journey mirrors that particular American alchemy of talent meeting opportunity.

His latest success, producing “Inamorata” by UK recording artist Carly Paoli (which recently entered the Top 10 on UK Music Week’s Chart), demonstrates that creative excellence doesn’t diminish with time when it’s built on genuine craft rather than fleeting trends.

The Price of Principle

The current crisis engulfing 60 Minutes would have been unthinkable under Hewitt’s stewardship, Diamond believes. The $20 billion lawsuit, the departures of Executive Producer Bill Owens and Wendy McMahon, the public accusations of editorial compromise all represent precisely the kind of institutional decay Hewitt spent his career guarding against.

“Because we are in America, we are blessed with the right to report fully and freely,” Hewitt once declared. “The best way to ensure that we go on having the freedom to publish and broadcast is to guard against self-indulgence.” His insistence that no one should be able to “label 60 Minutes stories as left, centre or right” wasn’t mere idealism but strategic wisdom about building lasting influence.

When Owens announced he could no longer “make independent decisions based on what was right for 60 Minutes,” he was describing exactly the kind of institutional pressure Hewitt understood would be fatal to the programme’s credibility. McMahon’s subsequent departure, citing fundamental disagreements about the programme’s direction, only deepened the sense that something essential was being lost.

What Power Actually Looks Like

The contrast between Hewitt’s quiet authority and today’s corporate theatrics reveals something crucial about sustainable leadership. True power, it seems, doesn’t announce itself through boardroom ultimatums or public relations campaigns. It accumulates through consistent decisions, authentic relationships, and unwavering commitment to core principles.

For those of us navigating leadership roles across industries, Hewitt’s example offers a masterclass in influence without ego. His ability to remain genuinely curious about carpet samples whilst simultaneously shaping global news coverage demonstrates that authority doesn’t require constant performance. Sometimes the most powerful thing you can do is simply be present, engaged, and authentic in whatever moment you’re inhabiting.

This lesson feels particularly relevant as we watch traditional power structures fracture across media, technology, and business. The old model of command-and-control leadership is proving inadequate for navigating complex, interconnected challenges. Hewitt’s approach (building trust through consistency, maintaining independence through principle, and wielding influence through service rather than self-promotion) offers a more sustainable path forward.

The Long Game

Diamond’s reflections on his neighbour arrive at a moment when media integrity faces unprecedented challenges. But they also remind us that the most enduring forms of success are often the quietest ones. Hewitt didn’t build 60 Minutes through grand gestures or corporate maneuvering. He built it through daily commitment to editorial excellence, one story at a time, one decision at a time.

The programme’s current struggles don’t diminish that legacy but illuminate it. They show us what happens when institutions drift from their founding principles, when short-term pressures overwhelm long-term vision, when the performance of leadership replaces its substance.

In an era obsessed with disruption and transformation, perhaps the most radical act is the kind of steady, principled leadership Hewitt embodied. Not leadership that seeks to dominate or dazzle, but leadership that serves something larger than itself. Leadership that understands the difference between being powerful and being effective.

As Diamond reflects on his remarkable journey from those elevator conversations to his continued success in music production, he’s certain that Don would never have resigned or backed down in the face of such pressures. In a world increasingly defined by retreat and resignation, that kind of quiet determination feels like exactly the leadership lesson we need.