Enjoy Before Returning: Why Some Brands Are Encouraging Returns

Looking at new words like “Social distancing” or “zoom hugs” we all agree that they are reflecting a new reality. We came across a word that, while is not new, it reflects a trendy consumers behaviour on the rise: wardrobing. If you wonder why some stores made items such as an expensive wedding dresses or Christmas decorations, unreturnable, is because of…wardrobbers. Purchasing, using, and then returning luxury clothing or gadgets to the store and claiming a full refund, is known as wardrobing. A form of return fraud, experts rank it in the same category with shoplifting. Expensive clothing, electronics, and even luxury cars are all subject to a 14 days return policy.

In contrast to those condemning returns, a recent marketing campaign on wardrobing won the Brand Experience & Activation Award and positioned DIESEL as one of the Eurobest 2020 Grand Prix Winners. At this point you might ask why some brands are encouraging returns and some don’t.

Could returns generate huge returns?

Amazon’s return policy was originally introduced to cultivate a customer-friendly image. Perhaps they never imagined that a friendly return policy could magnify consumers’ buying power, and, ultimately become a very expensive exercise, not only for them but for all retailers, with a $15 billion / year price tag for the fashion industry alone. Making it easy for shoppers to change their mind and send back items they don’t want, the return policy conditioned consumers across all brands to expect the same treatment and claiming their money back, became a consumers’ right. The giant Amazon decided to ban the wardrobbers ( shoppers buying clothes, wearing them for the occasion and repeatedly returning them within 14 days for a full refund).

Photo by Simon Bak

Does blacklisting works?

No. People still return clothes. Blacklisting the shoppers who are abusing their consumer’s rights, is one way of dealing with wardrobing, but fashion psychologists consider that this behaviour is routed into wardrobbers’ generation DNA. It’s a consumers’ behaviour and some brands start thinking that maybe is best to accept it. Diesel, for example, openly and resiliently accepted the reality of it, but took a different approach: the best way to fight it is to not fight it at all. They embraced wardrobing as something normal, and turned their return policy into a global campaign.

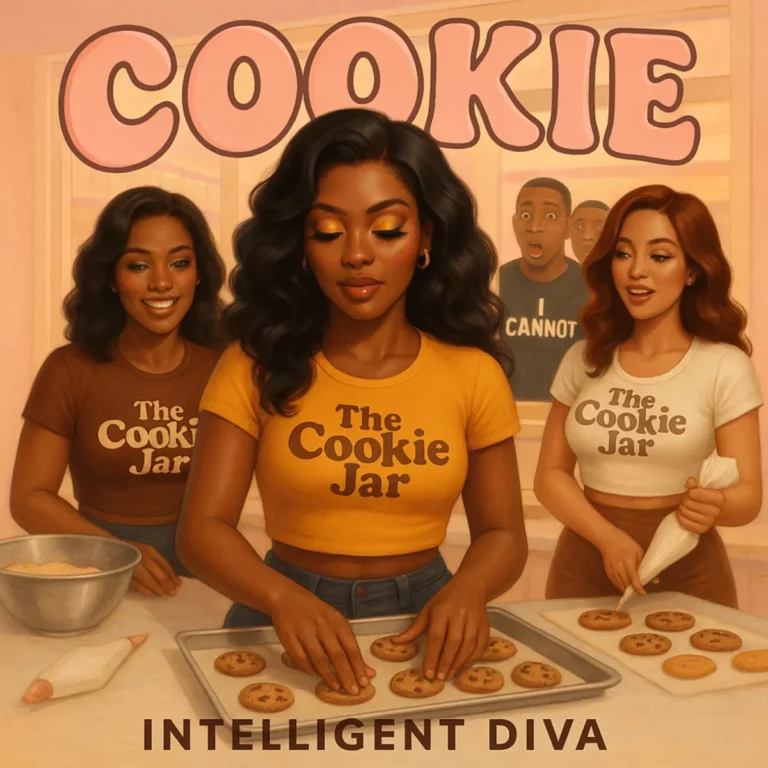

As seems that nothing can make people stop wardrobing, they organized exclusive fashion week parties inviting wardrobers to wear their cloths with the tag out (“all brands welcome”) and to turn people’s photos of wearing the clothes they want to return as valid “receipts” for when will return something they bought within the last 14 days.

ENJOY BEFORE RETURNING

Diesel embraced wardrobing and encouraged people to ENJOY BEFORE RETURNING. People’s photos with themselves wearing DIESEL item’s with the tag out counted as VALID discount coupons for their next purchase on ecommerce. The outcome?

People called us crazy. Competition called us crazy. Well, besides becoming the talk of town, the approach helped to actually REDUCE the Diesel returns by 9% globally and the sales went up with 24% GLOBALLY, where more than half came from new customers – people in the younger age groups who never considered DIESEL before.